Some trips are more than just travel plans. They come from a feeling you can’t quite explain. This visit to Nagaland was one of those. It felt like going back to where parts of me began. What followed were days filled with colour, culture, familiar faces, and moments that brought back memories while creating new ones I know I’ll carry with me.

This blog is also deeply personal because Nagaland is where I was born. I was born in Pfutsero, and because my father had a transferable job, my childhood unfolded across different parts of the state. I lived in and around Phek, Wokha, Mokokchung, Pfutsero, Kohima, and Dimapur, and I did my schooling across these towns. These places were not just stops along the way; they shaped how I grew up, the people I met, and how I understood community and belonging.

Nagaland is home to numerous indigenous tribes, primarily of Tibeto-Burman origin, each known for its distinct culture, language, and festivals. Tribes such as the Angami, Ao, Chakhesang, Chang, Konyak, Lotha, Rengma, Sumi (Sema), and Zeliang form the cultural backbone of the state, alongside recognised groups like the Kuki and Kachari. While every tribe maintains its own traditions and identity, English serves as the official language, and Nagamese acts as a common tongue across communities.

Growing up here, these differences were part of everyday life. The Angami, largely inhabiting the Kohima region, are known for their rich folklore and distinctive architecture. The Ao people are prominent in the Mokokchung district, where cultural practices and community life are deeply rooted. The Chakhesang tribe, a composite group that includes the Pochury community, is primarily settled in the Phek district and is known for strong agricultural traditions and cultural richness.

The Chang tribe inhabits the Tuensang area, also known as Mazung, while the Konyaks, the second-largest tribe in Nagaland, are recognised for their striking tattoos and a history that once included headhunting. The Lotha people belong mainly to the Wokha district and have their own dialect and customs. The Phom tribe is found in Longleng, the Rengma in parts of Kohima, and the Sumi (Sema) community in Zunheboto, each preserving their own ways of life.

Other tribes such as the Sangtam, Tikhir (recognised as a distinct tribe in 2022), Yimkhiung (Yimchunger), and Zeliang are spread across districts like Tuensang and Peren, adding to the diversity that defines the state. Over the years, many tribes have embraced Christianity, which is now an important part of daily life. Yet, the heritage of weaving, art, music, storytelling, and agriculture continues to thrive quietly, woven into everyday living rather than preserved as something distant.

Coming back now felt like reopening a part of my own history.

Day 1: Remembering History at Kohima War Cemetery

The journey began on a deeply reflective note with a visit to the Kohima War Cemetery after 35 years. Nestled in the hills, the cemetery stands as a solemn reminder of the pivotal Battle of Kohima fought during World War II in 1944. It honours over 1,400 Commonwealth soldiers, primarily British and Indian, who laid down their lives.

One inscription, etched in stone and memory, says it all:

“When you go home, tell them of us, and say, for your tomorrow, we gave our today.”

Standing there, surrounded by silence, flowers, and rolling hills, I felt gratitude, humility, and an overwhelming respect for history.

Day 2: The Colours and Spirit of the Hornbill Festival

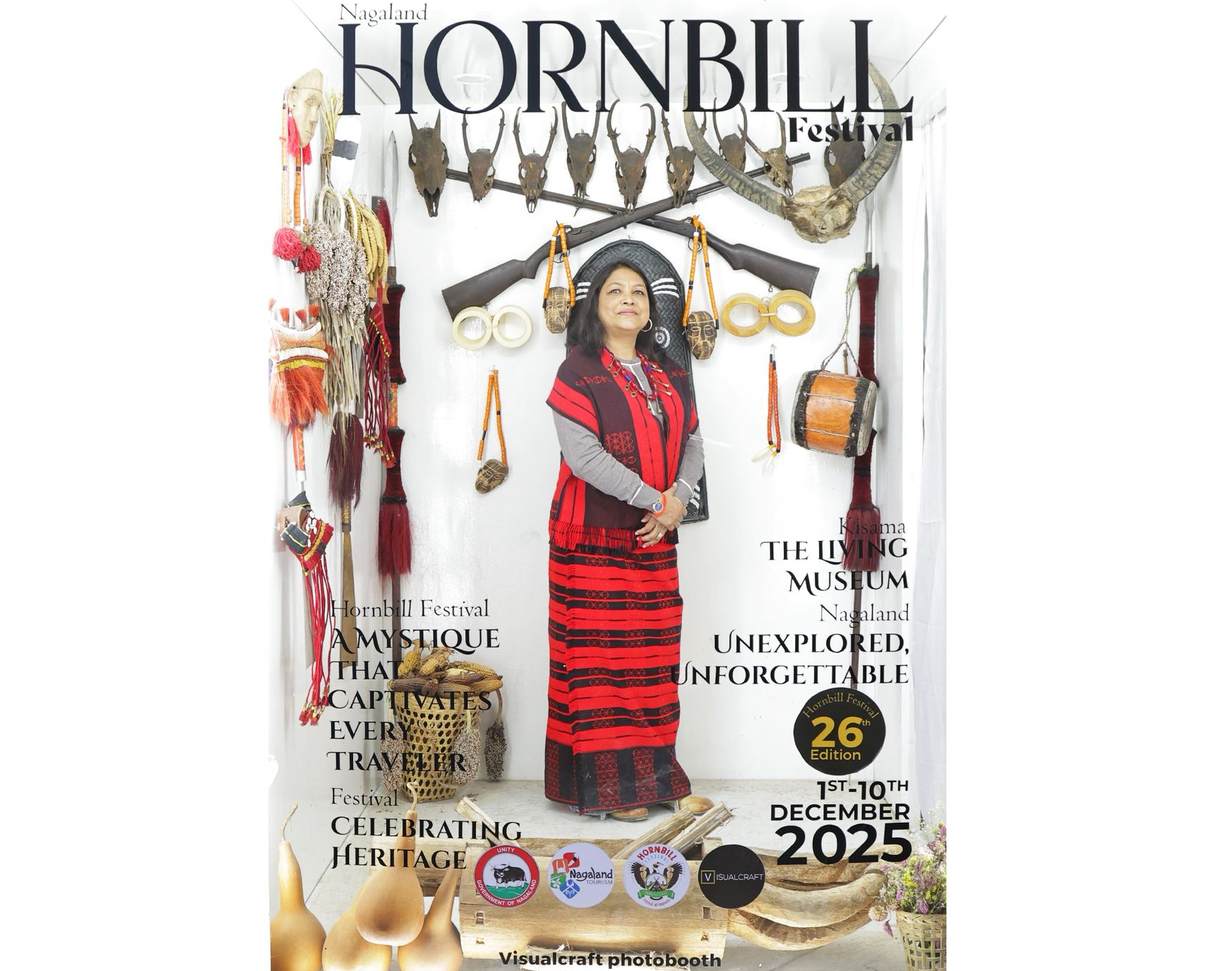

It is true when they say that Nagaland truly comes alive during the Hornbill Festival. Celebrating its 26th edition this year from December 1 to December 10, the festival is a vibrant showcase of the cultural identity of the Naga tribes. Named after the hornbill, a revered and colourful forest bird deeply rooted in Naga folklore, the festival is a celebration of unity, tradition, and pride.

From folk dances to traditional music, every performance felt like a living story passed down through generations. One simply cannot miss clicking a picture in traditional Naga attire. The multi-coloured ornaments, though simple in design, carry deep cultural meaning and elegance.

The theme for Hornbill Festival 2025, “Cultural Connect”, beautifully captures its essence by focusing on Naga identity, unity, and the preservation of living traditions.

Day 3: People, Culture, and Living Traditions

One of the most enriching experiences was learning about the Chakhesang tribe, a major Naga ethnic group named from an acronym of three linguistic communities Chakrü (Chokri), Khezha, and Sangtam (now known as Pochury). Primarily settled in the Phek district, they are known for their strong agricultural traditions, handicrafts, and cultural richness.

Meeting elders, interacting with locals, and witnessing everyday life reminded me that culture here isn’t curated; it’s lived.

Tasting Tradition: Zutho and Stories That Last

“Hangovers are temporary, stories last forever.”

And some stories come in bamboo mugs. Zutho, the traditional rice beer of Nagaland made from sprouted rice, is white, fermented, mildly sour, and aromatic. Often compared to Japanese sake, it plays an important role in celebrations and rituals across the state.

Sharing Zutho wasn’t just about tasting a drink; it was about sharing moments.

Nature’s Quiet Magic: Dzukou Valley

The Dzukou Valley is nothing short of breathtaking. Located on the border of Nagaland and Manipur, this high-altitude valley is famous for its rolling green hills, streams, and seasonal carpets of wildflowers, especially the endemic Dzukou Lily. The serenity and untouched beauty make it a trek worth every step.

Villages That Hold the Soul of Nagaland

Khonoma, Asia’s first Green Village, stands as a shining example of community-led conservation and sustainable living. Known for its warriors, master weavers, organic farming, and terrace cultivation, the village reflects a way of life lived in harmony with nature.

Jakhama, a Southern Angami village located south of Kohima, carries historical significance from the Second World War and today thrives through strong community values and traditions.

Dzuleke Valley, Kisama, Pfutsero, Dimapur, Mokokchung, Wokha, Zunheboto, and Phek each added their own chapter to this journey.

Coming Home

Nagaland is not just a destination for me. It is where I was born. Walking through places I’ve known for years, remembering childhood moments, and seeing them again after so long filled me with a quiet sense of happiness and gratitude.

Some places don’t need introductions. They already know you. And coming back reminds you exactly where you belong.